What is the optimal stretching dose?

Overview

This article presents the Stepwise Progression Method for static passive stretching, a structured approach I’ve taught over more than three decades of coaching. Though I have taught it for years, its name is a relatively recent invention, and one that occurred only after many students insisted I give it one. The essence of “stepwise progression” is simple: take small, measured steps rather than tackling everything at once. Each careful step becomes the footing for the next, forging a clear, lasting course toward your final aim. In this manner, progress remains steady without risking overtraining.

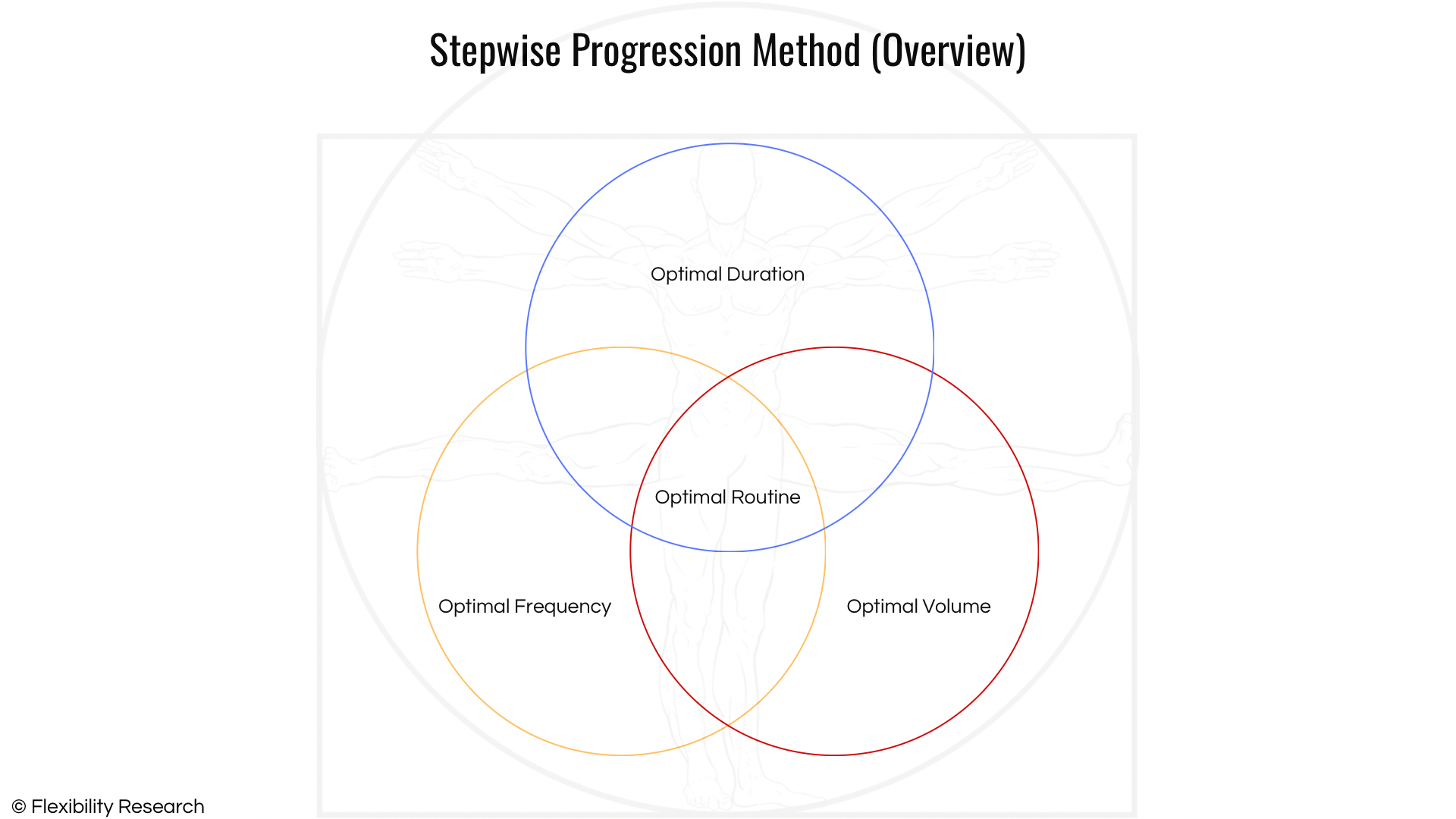

When put to use with static passive stretching, this plan tackles the main elements shaping progress: volume, duration, and frequency. Each is broken into small, workable steps, helping you pin down your best starting point for one element before moving on to the next. For example, you might gradually increase volume before shifting your focus to duration, and later adjust frequency. But there is no iron-clad rule to how you approach it; if duration or frequency seems simpler first, take that route. The real point is to change only one element at a time. In the long run, the exact sequence hardly matters, so long as you hold your attention and intent steady at every single turn, throughout the entire process.

Though I usually reserve this method for my students and clients, I’ve chosen to share it publicly because misguided advice on static passive stretching is flooding the Internet. I offer it now in the hope of raising awareness. Much of the advice given by stretching 'experts' treats everyone the same, which often fails or even works against many folks. My goal in revealing this method is to give the fitness community a more thoughtful, flexible tool. If you gain from it, I encourage you to share it with others. But please avoid claiming it as your own. The urge to puff up one’s ego is lamentable but easily sidestepped in our present culture.

Introduction

Recently, people kept asking me the same question: “How long should you stretch for the best results?” That thought carried me back, years ago, to a fitness conference. It was huge, the sort that can swallow you whole. The place pulsed with energy. Everywhere, people bustled in matching polo shirts, their chatter thick with new trends and jargon. I was there to explain why flexibility matters in karate, but my time to speak hadn’t arrived. Restless, I quietly roamed the wide halls, passing booths and stages. Then I came upon a session called ‘The Real Science of Stretching.’ It drew me in at once. The talk was just beginning, so I found a seat in the back, curiosity pulling me forward.

The man on stage was a young strength and conditioning coach, brand new to the long push of life. He wore a crisp suit, and his microphone sparkled like he had come from some shining TED talk. He moved with quick, uncertain vigour, as though the faith that fosters big ambition still ran hot in his veins. His gestures were swift and sharp, parting the air as if it were something he could shape in his hands. He paused, then spoke in a voice both firm and empty of doubt, announcing, “Stretching is worthless. But if you insist on doing it, don’t hold a stretch longer than five seconds, or you’ll risk injury.”

The coffee in my grip, set in a flimsy paper cup that cost too much, wavered near spilling, but I kept it steady in my hand. Useless? Five seconds? Those words clanged in my mind, fierce and uneasy, like nails rattling in a crate. For years, I had been sliding into the splits and kicking high without getting hurt. Now, don’t be fooled. I wasn’t born limber. That flexibility came from hard physical effort in long workouts, inch by inch, stretch by stretch, every day. 'Experts' often say thirty seconds will stretch a muscle enough, but that old bit of wisdom never worked for me. My body needed more. It took patience before my muscles released their hold upon me.

Yes, some folks manage well with holds no longer than five seconds. Yet from what I have carefully observed across the years, most people require more, maybe thirty seconds or even longer. Whenever I hear people claim that stretching is pointless, or that five seconds will suffice, or that holding longer will cause harm, it seems quite foolish indeed. It’s like telling a runner to settle for a lazy, unhurried shuffle and never dare a sprint. But I kept silent. For the moment, anyway.

The presenter stood before us like a preacher at the pulpit. His voice rang out with such conviction, each word so clean and final. He declared dynamic stretching as the lone path to real flexibility. He dismissed static passive stretching like a long-held old superstition favoured by the timid or unwilling. At best, he allowed, those stretches might serve as fleeting indulgences. He spoke of a looming, deadly peril he simply named “stretch-induced injury.” He described it as a shadow lying in wait for fools who courted disaster by holding poses too long. His words felt heavy and urgent; he pressed us to forsake the “old ways” and boldly welcome the new (or his version of it).

The trouble was the 'old ways' had always worked well. But the presenter insisted that his argument stood on solid proof. The PowerPoint slides arrived, one by one, snapping into place with a steady beat of unwavering urgency. Each was a collage of charts and graphs, shapes that hinted at something deep but left little behind, like footprints erased by the tide. All the 'data' came from the presenter's gym; he had only case studies that lacked the heft of controlled clinical trials or systematic reviews. It also hadn't been subjected to peer-review. (The problem with data that isn’t peer-reviewed is that it can easily be manipulated.)

When the talk ended, the presenter called for questions. The room stayed silent. You could feel the heavy weight of the hush, as though everyone weighed their words against the stillness that filled the room. I carried deep doubts about the strength of his data, and his experience. I raised my hand. He looked at me. There was a flicker there, a pause so slight it might have almost gone unseen. But it remained, a crack in his armour, a moment when his words somehow lagged behind the idea of being challenged, leaving him exposed for an instant. It passed swiftly, like a shadow sliding over a wall. He nodded, a gesture of obligation more than any open invitation

“Yes?” he said.

“Have you ever thrown a head kick?” I asked, my tone neutral but deliberate.

He blinked, visibly caught off guard. “No, but—”

“Ever done the splits?”

He paused. “Well, no, but—”

"And you never will if you're only stretching for less than five seconds at a time."

For a moment, he seemed suspended in thought. It wasn't as though he were wrestling with a question, but that the very act of deliberation was unnecessary. Then, with a shrug that mirrored the indifference of his words, he spoke.

“The splits are useless,” he said. His tone was unmistakably final. “And the only kick I care about is the one that sends the ball into the end zone.” He folded his arms across his chest. His stance wasn’t asking for approval. “My data proves all this. Static stretching is old nonsense that stupid people still cling to. Data doesn’t lie.”

He let his words stay in the air, slow and certain, like a hunter sure his prey had no escape. Then he smiled. It was a grin both measured and triumphant, belonging to a man who thought he’d already won. The hush in the room turned thick as nobody spoke. I could sense their watchful eyes on me, pressing my skin. But I held steady. My years of full-contact karate had taught me not to flinch at a simple war of words. Besides, this wasn’t my first run-in with a self-appointed expert peddling falsehoods about stretching.

“Well,” I said, keeping it light, “you need the splits, or near enough, to land a head kick. And kicking a football wins games, but head kicks end arguments.”

The audience chuckled. The presenter didn't.

I went on. “Your data are just case studies. They're anecdotes masquerading as evidence. The real facts, from controlled trials and meta-analyses, show that static stretching works better than dynamic stretching for increasing flexibility. Longer holds bring better gains. And above all, in all the piles of studies and papers, there’s no solid proof that proper stretching ever caused an injury.”

The room went quiet again. No one stirred. Every eye fixed on the presenter. He parted his lips like he had something to say, maybe a sharp line to cut the tension and end it. But no words came. He shut his mouth again and stood there, slipping further into the deep, tense hush. I began to feel a little sorry for him. Then he cleared his throat and gave an empty laugh. He was trying to convince himself he still had some control

“All right,” he said. His voice had changed. It was flat now, stripped of the sharp edge it had before. “Let’s move on. Who’s next?”

A few hands went up, slow and uncertain. He did not turn my way again. He gestured sharply toward someone in the rear. A few folks glanced at one another, joined by quiet and awkward chuckles. Some regarded me with raised brows, but I only shrugged and smiled.

During my own talk later, someone brought up the clash with the other presenter. I scanned the crowd, but he was nowhere in sight. I had hoped to find him, not to accuse him or cast blame, but to have a discussion. I wanted to set things straight, without anger or spite. Mistakes, if faced directly, often reveal truth, and truth is more important than winning arguments (though they often go hand-in-hand). My audience that day wanted to learn the optimal dose of stretching. They demanded honest answers. Not the lazy sort the earlier presenter had offered with a shrug, five seconds or nothing at all. The answer to this question is not simple. The truth has many layers, and I will share them here.

By the way, I speak of this episode with the presenter not because it’s entirely unusual, but because it isn’t. This is the sort of event that occurs almost every day. On social media, errors like this spread like wildfire. People who understand nothing about the science of flexibility still pretend that, somehow, they do. They speak with authority they haven’t earned. They sow half-truths or blatant lies about static passive stretching. They hold up cherry-picked anecdotes and loudly proclaim them as ironclad proof. When genuine science appears, they take flight. They don't pursue the truth but cling to their version of it. When you challenge them, they ignore you. Your comments get deleted, and they quickly block you. It's a pattern, and it always unfolds exactly the same whenever pseudoscience appears. It can be draining. But this pattern must be opposed wherever it appears.

What is the optimal stretching dose?

Static passive stretching is everywhere. It features heavily in sports, physical therapy, and in the habits of those seeking better movement. But for all its presence, a question lingers: what is the right dose to make it work best? The answer is murky, a fog that hangs thick even though bright skies beckon in other parts of physical fitness. Consider aerobic and resistance training. We know how to condition the lungs and how to build muscle. Much is written about pushing the heart to last longer and making biceps grow. But, for stretching, we continue to fumble. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) offers simple advice: stretch two to three times each week. Hold it where the tension pulls but stays short of pain, for 15 to 30 seconds per stretch. Repeat that two to four times for each muscle group [1]. A neat prescription, sure. But it’s one that stands on shaky ground. Much of the proof leans on frail studies: randomised trials that aren't wholly sound, flawed designs that leave questions unanswered, and observations that barely scratch the surface [2].

Researchers have long overlooked the quest for the right dose of static passive stretching to improve flexibility. The findings appear scattered and often clash. A group of researchers tried to unravel the link between stretch intensity and body positioning, exploring their possible impact on range of motion (ROM) [3]. But their efforts struck a barrier borne of scant and inconsistent evidence, and they failed to reach clear conclusions. Another team chose a different path, sifting through 18 studies in a meta-analysis. They discovered that static passive stretching increased hamstring flexibility among young adults [4]. However, their work left one lingering question: which precise dose is required for the best result

In another meta-analysis, the focus shifted to calf muscles. There, the researchers saw that static passive stretching boosted ankle ROM [5]. The extent of improvement did not falter, whether weekly stretching volume was low (less than 50 minutes), moderate (50-84 minutes), or high (more than 84 minutes). In another meta-analysis, the researchers delved into time’s impact, seeing how duration could shape outcomes in many subjects [6]. They compared weekly stretching regimens of five to ten minutes or more to those under five minutes. The findings showed that longer stretches delivered better gains in flexibility. A systematic review of 32 studies supported this, revealing a firm link between greater stretching time and improved flexibility. But the authors observed no major gap among low-, moderate-, or high-intensity sessions [7]. Another study echoed that conclusion. Stretching harder did not produce much difference [8]. Forcing yourself past discomfort, even into pain, is not always the surest way to boost flexibility.

A more recent review took another look at static passive stretching, both the type used in the moment (acute) and the type used over time (chronic) [9]. The findings revealed that old-fashioned stretching, done right, made you more limber. Stretch a bit for a brief spell, and you improved immediately, albeit for a short period. Stretch more over weeks, and you remained more flexible. Flexibility earned from static passive stretching endures; it sticks with you. The review found that the stretch’s intensity didn’t matter. Nor did age, sex, or experience. Young or old, man or woman, novice or seasoned pro, it worked all the same. Even how often or how long you stretched each week didn’t seem to shift much in the grand scheme. Stretching simply worked.

That review also revealed a pattern: the stiffer a person is when they start, the greater their progress. Tighter muscles increase flexibility quickest, and none more so than the hamstrings. For example, the legs made rapid progress. The back, though, experienced slower changes. The body, it seems, has its own set of rules, with each muscle group following its own rhythm. The review also showed that stretching works best with steady practice over a long period of time. Four minutes per session brought the best acute rewards, and just ten minutes a week was enough to create lasting changes. The lesson here is one of balance. Stretching should be like seasoning rather than the main meal; it's about adding just enough, not too little, not too much.

The truth is, no one knows if the ‘optimal dose’ revealed to us by research is the genuine peak of human capacity or just a shadow cast by the way we’ve studied it. Most of what we’ve learned leans toward brief durations, stretches lasting only two and a half minutes a session, adding up to twelve and a half minutes a week. Greater improvements in flexibility, achieved through longer hold durations and observed by coaches during real-world training, have created a mismatch with the evidence found in scientific research. But the tide is turning. Some researchers are pushing further, reaching for what was once unthinkable, such as stretches lasting up to an hour a day. They’re breaking the mould, questioning if we’ve been setting the bar too low all along [10-14, 15].

In 2022, a group of researchers took on this question with purpose [14]. They turned their attention to the calf muscles, holding them in a steady stretch for an hour each day, with the knee locked straight. The results showed participants gained real increases in ankle dorsiflexion ROM, outstripping the progress seen with shorter stretches of ten or thirty minutes a day over six weeks. It seems the longer the stretch, the greater the change. This is an observation I have made many times over my thirty-plus years of teaching flexibility. But while the idea is simple, the truth of it is not yet settled. This isn’t just a matter of “loosening up.” It’s about forging real, lasting changes in the makeup of muscles and tendons. Earlier studies missed this point. They failed to use the long, high-volume stretching routines needed to show these deeper adaptations [16,17]. What we need now is clarity; we need studies done with purpose, utilising stretches that last longer and subject the tissues to greater tension. We need research that presses hard to see if frequent, prolonged stretching can truly reshape the body’s limits. Most of all, we need to know the why and the how. What happens in the muscle? What changes in the connective tissue make better flexibility possible? These are the answers we are still yet to find in research. But there are ways in practice that each person can get to get close to the truth for their unique body.

Determining what is enough part 1: volume (how much)

Many people still find it difficult to figure out the best amount of stretching that works for them. I was fortunate to have discovered the answer to this problem for myself at an early age. When I was a boy in the dojo, learning karate, one lesson came at us hard and never let up: discipline. Everything had structure, a nod to the martial art’s military roots. Even stretching. At the start of each class, we stretched every major muscle group twice, holding for thirty seconds each time. After that came the dynamic stretches; we did kicks and leg swings, moving with greater height and speed with every repetition. My instructors said this exercise selection wasn’t random, but that it came from science mixed in with years of seeing what works (and what doesn’t) in practice. In the dojo, you didn’t ask questions. Certainly not during the class, anyway. But later, when the day was done and the quiet of night crept in, my mind began to wander. And I wondered.

I stretched when I was alone in my bedroom. No instructors, no rules, and no lines to follow. Thirty seconds passed. I thought, what if I held this longer? What if I didn’t stop at just two sets? After all, there was no one telling me I couldn’t. So, I kept at it. I slid toward the side split. My adductors fought back at first. The initial set hurt. The second set eased something. By the third, my body began to yield in a way I didn’t expect. I felt something shift, something I couldn’t name. I stretched further. Four sets. Five. Each time, I pressed on, finding a new boundary I hadn’t met before.

In the next class, I told my instructors about my experience. Disappointingly, they dismissed it as a fluke and gave me the same answer they always gave: two sets of thirty seconds are best. They said this was the standard based on research and practical experience. My peers nodded, content to accept this explanation. I watched and listened, but something felt off. It wasn’t rebellion that stirred in me, but rather a quiet, stubborn feeling, like my body was telling me a different truth. I couldn’t ignore the release I had felt in my muscles and the steady progress that had come with it. So, I began to experiment carefully and quietly in my own time. I didn’t set out with the intention to prove my instructors wrong. I just wanted to know what was best for me.

As the years passed, and I grew older, the questions in my mind grew sharper. I sought answers wherever I could find them. I sat in seminars and clinics, listening to the experts of the time. In the evenings, after my stretching practice, I devoured textbooks and research papers. Every word, every page, was a thread I wove into my understanding. In time, I found myself at the front of the training hall. At first, I lingered at the edges, helping seasoned instructors, watching how they taught, learning their ways. By the mid-1990s, still in my teens, I was leading my own classes in the dojo. I carried the voices of my teachers with me, their lessons etched deep. But alongside them, I bore the weight of countless nights spent alone, practicing and learning in silence and forging my own path. I taught my students to question everything (including me), to feel their own way forward, to trust their bodies, and not bow to rules they didn’t understand. Back then, I didn’t give this approach a name. Looking back now, I suppose calling it something like the “Stepwise Progression Method” might be an accurate label. That's the name I'll use for the purposes of this article. But names don’t matter; details do.

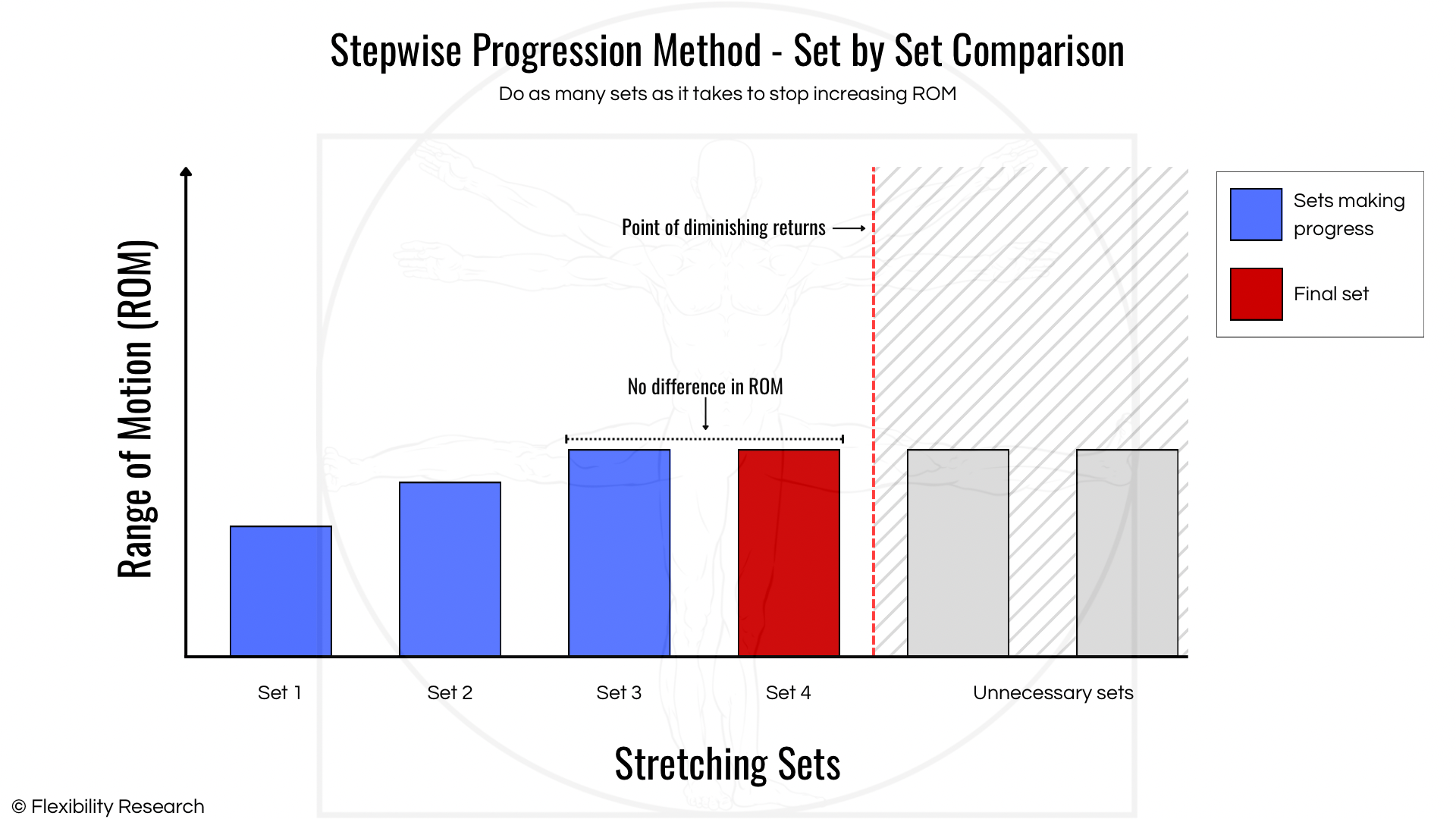

The method is simple. Stretch, rest, stretch again. Only do as many sets it takes for you to stop seeing progress. Push just far enough to meet the limit of what you can do that day, and then stop. The rules are few but they’re important. No two bodies are the same, and no two days feel the same. What matters most is a sharp eye and ear turned inward, catching what your body whispers in the moment. Intelligent exercise selection also forms part of this method.

The dojo was a place where time was at a premium. Classes brimmed with sparring, kata, and technical drills. So, each moment had to count. In my classes, I told my students to focus only on stretches that mattered most for karate: the front and side splits. The first set established a baseline. Thirty seconds holding, thirty seconds resting. (Or switch sides when doing the front splits.) Then stretch again. If the second set didn’t produce more ROM than the first, they would stop. But if the second set went deeper, they’d do a third. If that brought more ROM, they’d do a fourth. And so on. Some days, three sets were enough. Other days, they’d find progress through six or seven. The central rule was simple: when your most recent set gives nothing more than the last, stop and move on. By comparing one set to the next, instead of following a fixed number of sets given by an instructor or written in guidelines, you can figure out the right time for you to stop that stretch for the day.

Determining what is enough part 2: duration (how long)

I was never born with the gift of natural flexibility, but the splits became a central goal of mine as a young karateka. Bill Wallace, my most influential teacher, often spoke of how flexibility tied to speed and power, how a body that could bend and yield struck faster and harder. His words stayed with me. I wanted to be faster, stronger, and better, and I swore to myself I’d achieve that ambition. But like most things that matter in life, the road wasn’t easy. Stretching became a quiet fight, a steady clash with the stubbornness of my own body. In the beginning, I held each stretch for thirty seconds, just as my instructors said to do. But my muscles held their ground, tight and unyielding, defying my efforts. It was maddeningly slow work. The progress was so small it seemed like none at all. I started to see that thirty seconds wouldn’t cut it for me, but I didn’t know how much more I needed or even how to tell if I was getting anywhere. Frustration came, but it didn’t break me. Instead, it pushed me. If this was the limit, then it was time to test it and see what else I could do.

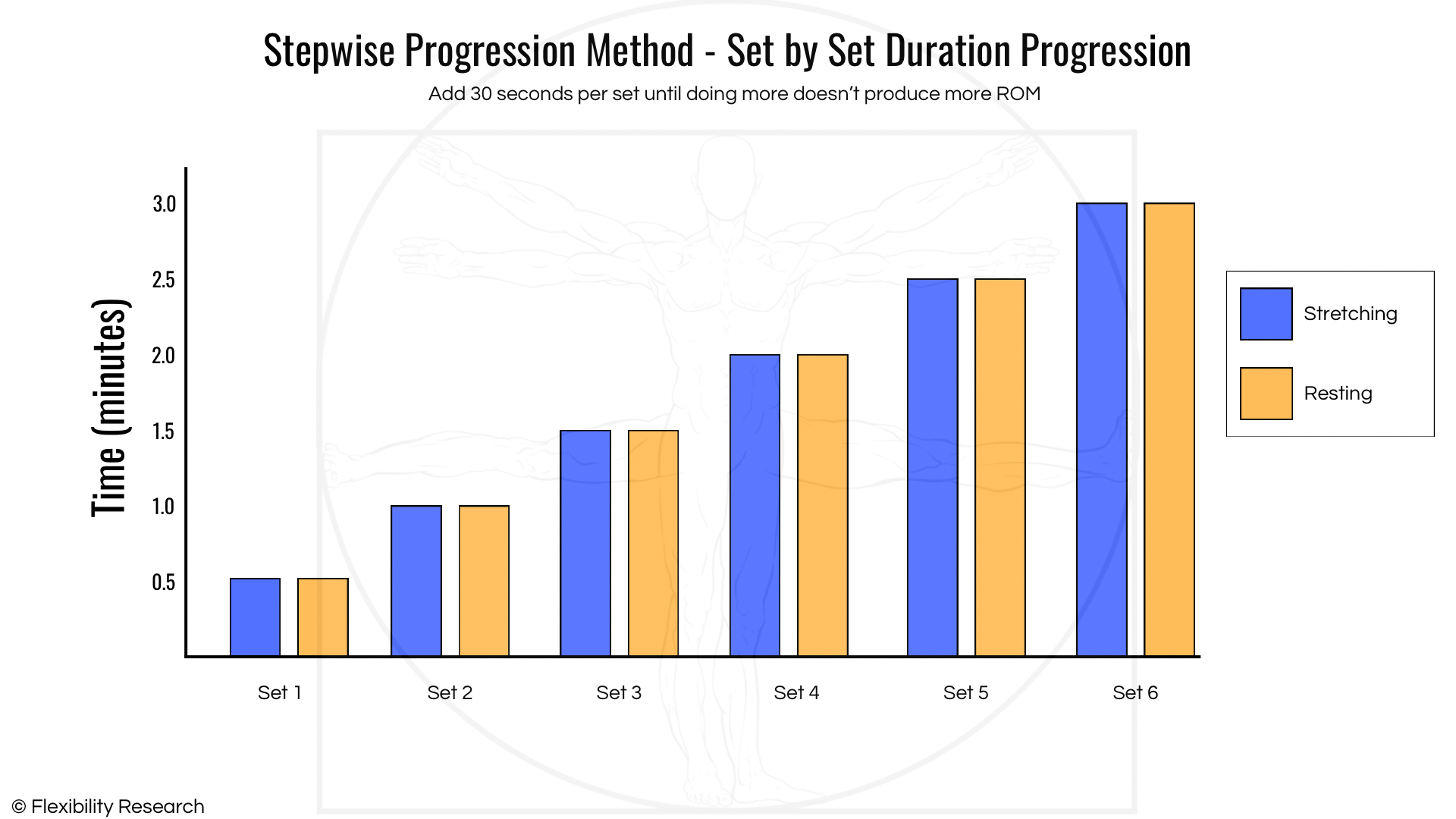

I started with a simple idea: hold each stretch for thirty seconds, adding another thirty seconds each week. Just like deciding the best number of sets to do in the Stepwise Progression Method, this was a useful way to find out the ideal stretching time for each person. It was a steady plan and something I could adjust as I went along. There were no sleek note-taking apps back then. Instead, I used a good ol’ fashioned no. 2 pencil and paper notebook. After each stretch, I wrote down how I felt, both in my body and my mind. (This is something I strongly recommend you do, too.) At first, the results were dull and a little disheartening. Thirty seconds almost felt like nothing, as if my body barely noticed. The stretch came and went, faint as a whisper, leaving behind no trace worth remembering. But I kept at it. By the second week, holding for sixty seconds, I started to notice quiet changes. My muscles let go in ways they never had before. My adductors, which had been stiff and stubborn, began to ease like old gears grinding back to life. Even after just that second week, my kicks became quicker, lighter, and cleaner. It was as if my body was finally starting to hear what I was asking from it.

By the third week, holding for ninety seconds, the act took on a new gravitas. The stretch became deliberate, a slow plunge into discomfort that, strangely, held meaning. It wasn’t just a movement of the body anymore. It was a test of my limits, a journey to where the real tension inhabited, buried deep in muscle and bone. At week four, I was holding the stretch for two minutes. At this mark, I felt like I was edging closer to the truth of my physiology. Two minutes was the line where my body, at last and completely, eased into the stretch. I saw, then, that it wasn’t about forcing anything. I simple needed to give my body the time it needed to yield and let go. Less than two minutes, and my body felt locked. But I wasn’t satisfied to stay at two minutes. There was a whisper on the edge of this discovery. By week six, I’d stepped into untested ground, holding each stretch for 180 seconds. I sought even greater progress. However, past the two-minute mark, I found myself at a strange juncture where effort turned sour, yielding restlessness rather than reward. I was met with greater resistance from my body. My muscles flared in pain and my mental focus splintered. It was too much. Two minutes was my sweet spot.

However, I noticed something strange. Others in the dojo responded differently, and in ways I hadn’t expected. I shared with them my methods, and some took to them like water. Their longer holds (sometimes three or four minutes in duration) unearthed progress I hadn’t seen and unlocked doors I thought were impassable. It struck me then that there wasn’t a universal map or a single formula. Flexibility is a journey, one on an unmarked road that we must each find and walk alone. Still, some people found it hard to hold a stretch for several minutes during their first set, even though they understood this was the best length of time for them at that point in their training. I remedied this issue by breaking the work into steps of five sets, each one building on the last. The first set lasted thirty seconds, then a minute, then a minute and a half, and on it climbed until the person was holding the final set for several minutes. Again, they were instructed to stop if their most recent set produced no greater ROM than the previous set. I also wove a simple rule for recovery into this plan: rest as much as you stretch. Thirty seconds of effort means thirty seconds of rest. Two minutes of strain demands two minutes to relax and breathe, and so on. This rhythm brings a balance that feels natural. Allowing your body to rest and relax after stretching your muscles to their fullest helps you stay ready and focused for the next set.

Determining what is enough part 3: frequency (how often)

Watching my karate students stretch, I thought of a garden. Each class they attended was like water on dry ground, coaxing growth from what lay dormant. The ones who came more often flourished, as a well-tended plant does, thriving under steady care instead of gambling on the whims of rain. Stretching, like gardening, demands patience. Seeds don’t sprout overnight. Flexibility doesn’t come from a single reach toward your toes. But the students who showed up, class after class, week after week, proved that progress is slow, steady, and sure. They stretched further and held positions longer. And in those small, deliberate acts, they grew. Their bodies transformed like soil turned fertile, a barren plot becoming lush. Their discipline reminded me that growth isn’t born of grand gestures but of the small, steady tending to potential. The students who came less often, though they showed some progress, were like plants left too long without water. When they returned, they moved with a kind of stiffness, as if weeds had grown in their place or the soil beneath them had dried and cracked. Their growth continued but was slower, hesitant, and uneven.

Another sight made the analogy come alive. The students who stretched more often learned more about their own bodies. They grew aware of every muscle and joint, like a gardener who knows the needs of each plant in their care. They saw how shifting a posture sharpened the stretch, how to balance effort with grace, and how to breathe through discomfort and make it endurable. It was no different than the gardener learning when to prune, when to feed the soil, and when to move a plant to stronger ground. Their regular attendance went beyond routine and became understanding. It brought mastery. Casual effort did not compare. Over the course of many weeks, the difference was clear. Those students who attended more classes dropped lower in their splits, kicked higher, and moved with increased certainty. The others, though no less skilled at the outset, trailed behind.

Although some research points to two or three weekly stretching sessions bringing clear and measurable gains, many people note that a daily habit gives the longest-lasting rewards. Indeed, it comes from steady, repeated work that muscles and connective tissues slowly adjust, gradually expanding our range of motion and enriching our general muscle function. By committing to a daily stretch routine, you keep your momentum, strengthen motor patterns, and grow a keener awareness of your body. Over time, you will see that the stiffness and soreness gathering from daily tasks start to noticeably fade, leaving you feeling lighter and more agile. Furthermore, a daily stretching practice grants clear mental rewards, planting a sense of calm and easing the strain that can gather in both the body and the mind.

That being said, a daily stretching routine is not optimal for everyone. To find the frequency that best serves your goals, you can take the approaches already discussed in this article and make them your own. Begin with a pace that feels manageable, one you can maintain without faltering. (It's better to stay the course than to push too hard and burn out.) Let each session be deliberate: focus on the mechanics of your movements, keep them measured and precise, and breathe with purpose. These things, done well, will make your efforts count. Keep a journal and write down every session. Record how hard it felt and what changed; did your muscles stretch easier, did the tension ease? Include any signs your body gave you, good or bad. Listen to your body as it speaks in terms of tightness, soreness, or no change at all. Hear it and adjust your course as needed.

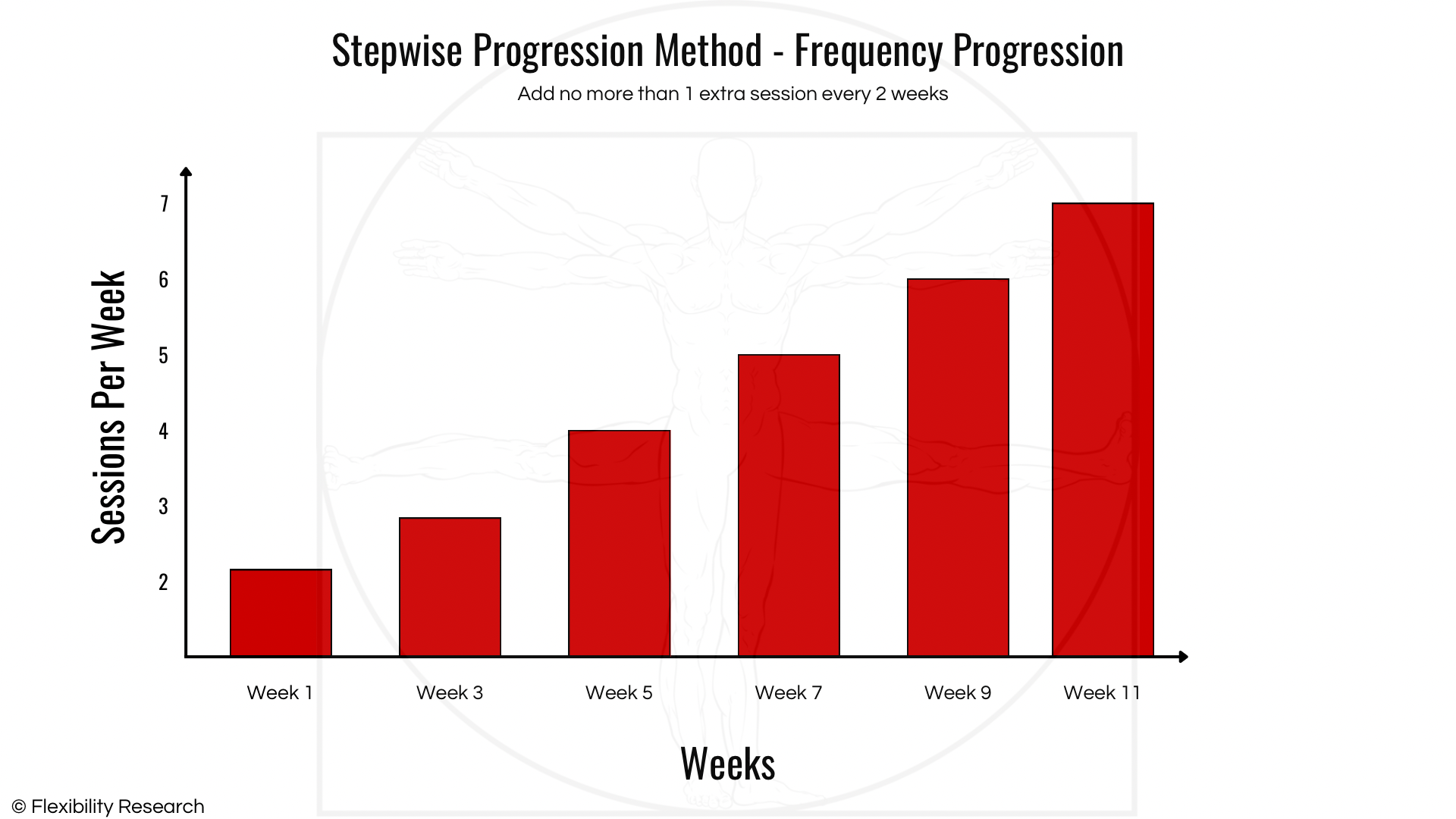

For the first two weeks, aim for two sessions each week. This is your starting point, a chance to see how your body responds to the stretching. If, by the end of the second week, you feel strong and you're without pain, take that as your signal to move forward into the third week. In the third and fourth weeks, add a third session to your flexibility practice and see if it makes a difference. Even a small gain in flexibility means your body favours three sessions over two. But this is where you must pay attention. Watch your recovery closely. If your body doesn’t become stiffer, sorer, or more tired, then you’re ready to add a fourth session in week five. This is where the point of diminishing returns shows itself for many people. You might feel it as the gains slowing down or fatigue building up. Pay attention to mental and emotional symptoms, too. Restlessness, boredom, a shorter temper, difficulty sleeping, and cynicism toward stretching might seem small, but they are signs that you need to ease off before you push too far.

Understand that as you move deeper into a particular range of motion, your plateaus will last longer. You have to spend more time and energy convincing your tissues and nervous system that the new ROM is safe and won't hurt you. Other than that, the cardinal rule of stretching progression is simple: if you keep improving and feel no added strain, either physically or mentally, you can do more. Add sessions slowly, every couple of weeks. But this takes a clear head and honesty. You must know when increased effort pays off and when it costs too much. The trick isn’t just working hard. It’s knowing when enough is enough.

There are signals that should prod you to reconsider raising your stretching frequency, or even to reduce it. If you notice that your flexibility has hit a lull, or worse, slipped in spite of extra training sessions, this is evidence that your approach may be damaging. This is why objective measures for tracking progress are priceless. Tools such as a metal tape measure can help gauge how far your hips rest from ground in the splits. Likewise, yoga blocks provide a clear measure; using fewer blocks while you get closer to the floor is a simple and direct method to mark ongoing progress. For sharper data, a digital goniometer can study joint angles in photographs, and numerous apps exist that make this process accessible.

Beyond objective measurements, it's crucial to listen to your body. If your sessions feel like they are dragging on, you experience lasting muscle or joint aches, your skill in other pursuits declines, or you grow consistently drained and weary, these cues suggest you must lessen your stretching schedule. Stay aware of the way your mind and body react to shifts in your habits. For many folks, a single daily session usually hits the sweet spot, but this is not a scientific law. Your best schedule relies on many elements, such as your present flexibility, how intensely you stretch, what other training you do, how well you sleep, the demands of your work and home life, the strains on your body, your age, and other factors like stress or diet. It is wise to keep in mind that what suits you today might not serve you always. Your ideal measure of stretching remains fluid, not fixed; it will shift over your life. Watching these changing factors is fundamental for making sure your practice stays potent.

Closing words

Over time, I learned to heed my body in ways I never had before. Some sensations became signposts. Pins and needles signalled danger. Numbness was a warning. Even boredom, slight as it seemed, was a sign that a stretch had run its course for that day. I learned never to ignore those signals; I took them as guides, forever adjusting and fine-tuning my approach. I implore you to do likewise. The goal is to stretch wiser, not harder.

Remember that the optimal stretching dose demands a measured tuning of duration, volume, and frequency, three linked forces that must unite for real progress. Adjusting these points to each person’s unique needs, aims, and physical state is vital for anyone seeking the full rewards of flexibility training and strong physical gains. Volume, the total load of stretching, lays the bedrock. It includes how many stretches you perform and how many sets you complete of each stretch in that session. Though higher volumes often bring bigger improvements in flexibility, they also raise the odds of soreness. Too little leads to a standstill. Finding the right middle ground calls for a watchful eye: push too far, and muscles strain; hold back too much, and progress stalls.

Duration, the time you hold a stretch, is another central concern. Studies show that holding for 30-60 seconds can yield solid gains in flexibility. But this window is not a fixed rule. Novices may do well with brief holds, while seasoned practitioners might need longer sessions to push their range and increase muscle extensibility. The right duration is personal and adapts as you progress. It can begin modestly and expand with time and patience. However, once you have reached a given level flexibility, less time and effort is needed to maintain it.

Frequency is how often you stretch. Daily work can spark change, especially for those with stiff joints or bold goals. But not everyone needs that intensity; for some, two or three sessions a week suffice. Others, with tighter muscles or precise flexibility targets, may require more frequent effort. The proper pace varies widely, shaped by each person’s starting point and ability to recover. Tune it to match your body’s capacity.

Honing these variables (duration, volume, and frequency) forms the heart of stretching, revealing the right “dose.” Age, fitness level, and personal aims shape what best suits each individual. By watching progress and resetting these levers as necessary, you keep the practice both potent and enduring. Thus, stretching rises beyond simple mechanics and becomes a path for amplifying flexibility and sharpening total physical ability. It weaves the body and mind into a pursuit of lasting progress.

What started as a boy’s resolve to reach the ground in the splits turned into something much more profound. It became a system, one that I have since shared with countless others who have achieved their flexibility dreams. This approach eventually led to me mastering the splits. It also taught me patience. It reshaped my notion of limits, not as barriers, but as signs of possible progress. The dojo was where I first learned the art of flexibility training, but the lessons carried far beyond its walls. Flexibility, I discovered, was about more than just physical motion. It was a symbol of resilience, of the power to bend without breaking. It was about persistence and the quiet force of discipline. And in the steady, careful act of stretching my limbs, I happened upon something lasting: a method, yes, but also a viewpoint. One that showed me how to move and how to truly live. May it do the same for you.

References

[1] Garber, C. et al. (2011) 'American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise', Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 43(7), pp. 1334-1359.

[2] Pate, R. et al. (eds.) (2012) Fitness Measures and Health Outcomes in Youth. Pilsbury; Washington DC.

[3] Apostolopoulos, N. et al. (2015) 'The relevance of stretch intensity and position: A systematic review', Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1128.

[4] Medeiros, D. et al. (2016) 'Influence of static stretching on hamstring flexibility in healthy young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis', Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 32(6), pp. 438-445.

[5] Medeiros, D. & Martini, T. (2018) 'Chronic effect of different types of stretching on ankle dorsiflexion range of motion: Systematic review and meta-analysis', Foot, 34, pp.,28–35.

[6] Thomas, E. et al. (2018) 'The relation between stretching typology and stretching duration: The effects on range of motion.' International Journal of Sports Medicine, 39(4), pp. 243–254.

[7] Arntz, F. et al. (2023) 'Chronic effects of static stretching exercises on muscle strength and power in healthy individuals across the lifespan: A systematic review with multi-level meta-analysis', Sports Medicine, 53(3), pp. 723–745.

[8] Konrad, A. et al. (2024) 'Chronic effects of stretching on range of motion with consideration of potential moderating variables: A systematic review with meta-analysis', Journal of Sport and Health Sciences, 13(2), pp. 186–194.

[9] Ingram, L. et al. (2024) 'Optimising the dose of static stretching to improve flexibility: A systematic review, meta-analysis and multivariate meta-regression', Sports Medicine.

[10] Warneke, K. et al. (2022) 'Using long-duration static stretch training to counteract strength and flexibility deficits in moderately trained participants', International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(20), 13254.

[11] Warneke, K. et al. 'Influence of long-lasting static stretching on maximal strength, muscle thickness and flexibility', Frontiers in Physiology, 13, 878955.

[12] Warneke, K. et al. (2023) 'Sex differences in stretch-induced hypertrophy, maximal strength and flexibility gains', Frontiers in Physiology, 13, 1078301.

[13] Warneke, K. et al. (2023) 'Comparison of the effects of long-lasting static stretching and hypertrophy training on maximal strength, muscle thickness and flexibility in the plantar flexors', European Journal of Applied Physiology, 123(8), pp. 1773-1787.

[14] Warneke, K. et al. (2023) 'Improvements in flexibility depend on stretching duration', International Journal of Exercise Sciences, 16(4), 83.

[15] Warneke, K. et al. (2022) 'Influence of long-lasting static stretching intervention on functional and morphological parameters in the plantar flexors: A randomised controlled trial', Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 10, 1519.

[16] Freitas, S. et al. (2018) 'Can chronic stretching change the muscle-tendon mechanical properties? A review', Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 28(3), pp. 794–806.

[17] Panidi, I. et al. (2023) 'Muscle architecture adaptations to static stretching training: A systematic review with meta-analysis', Sports Medicine (Open), 9(1), 47.